21 March - 18 April, 2020

Ghosts in the Museum

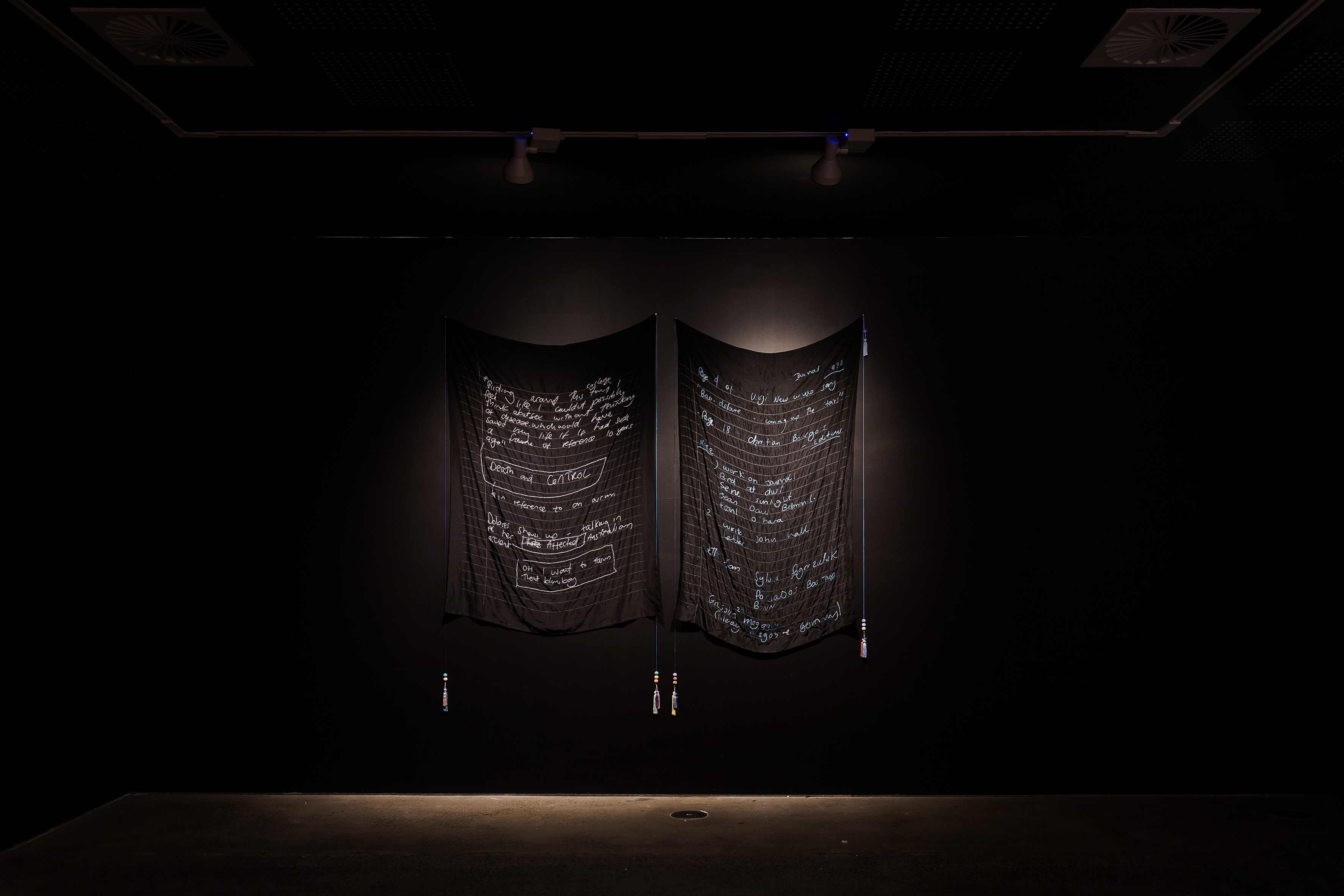

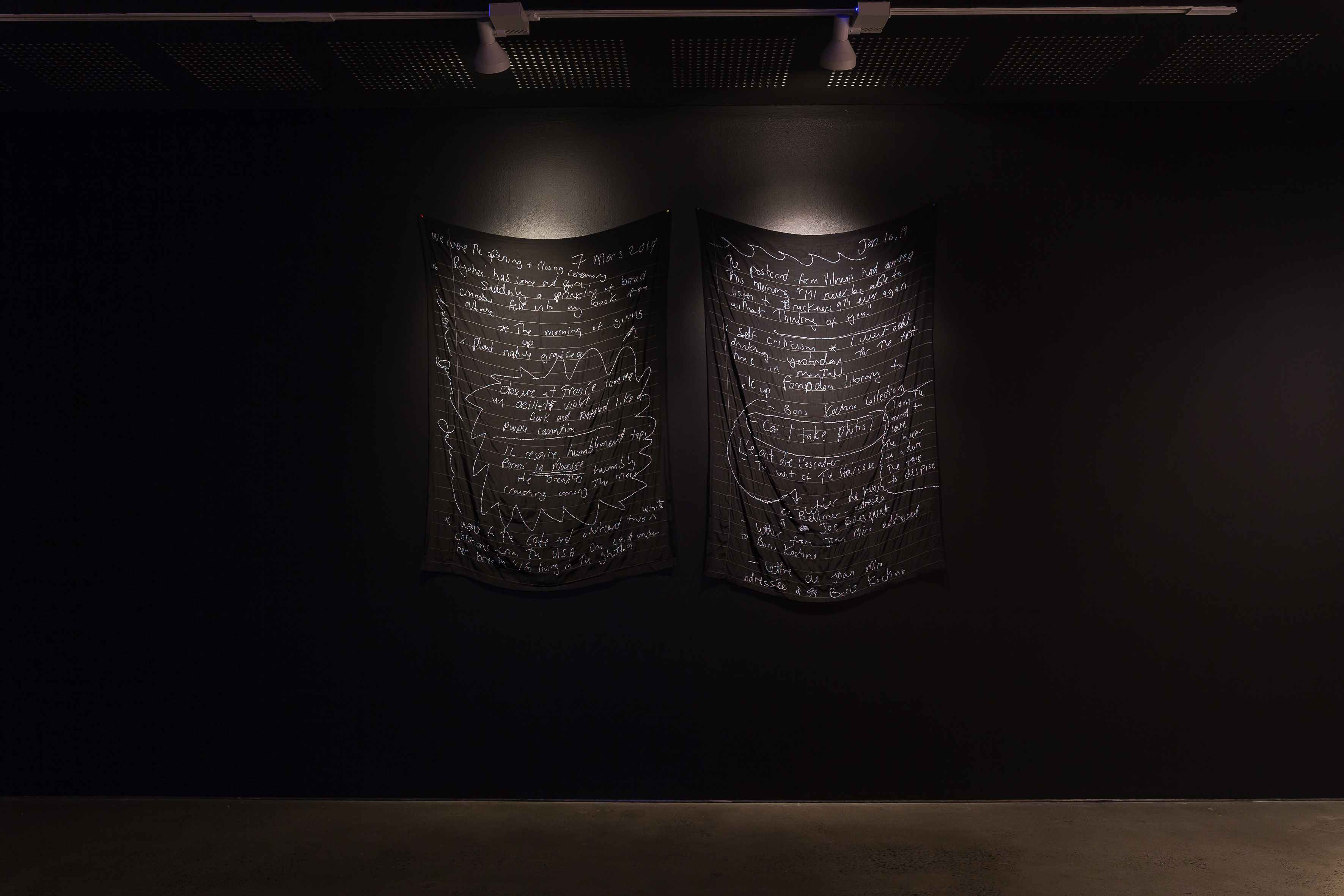

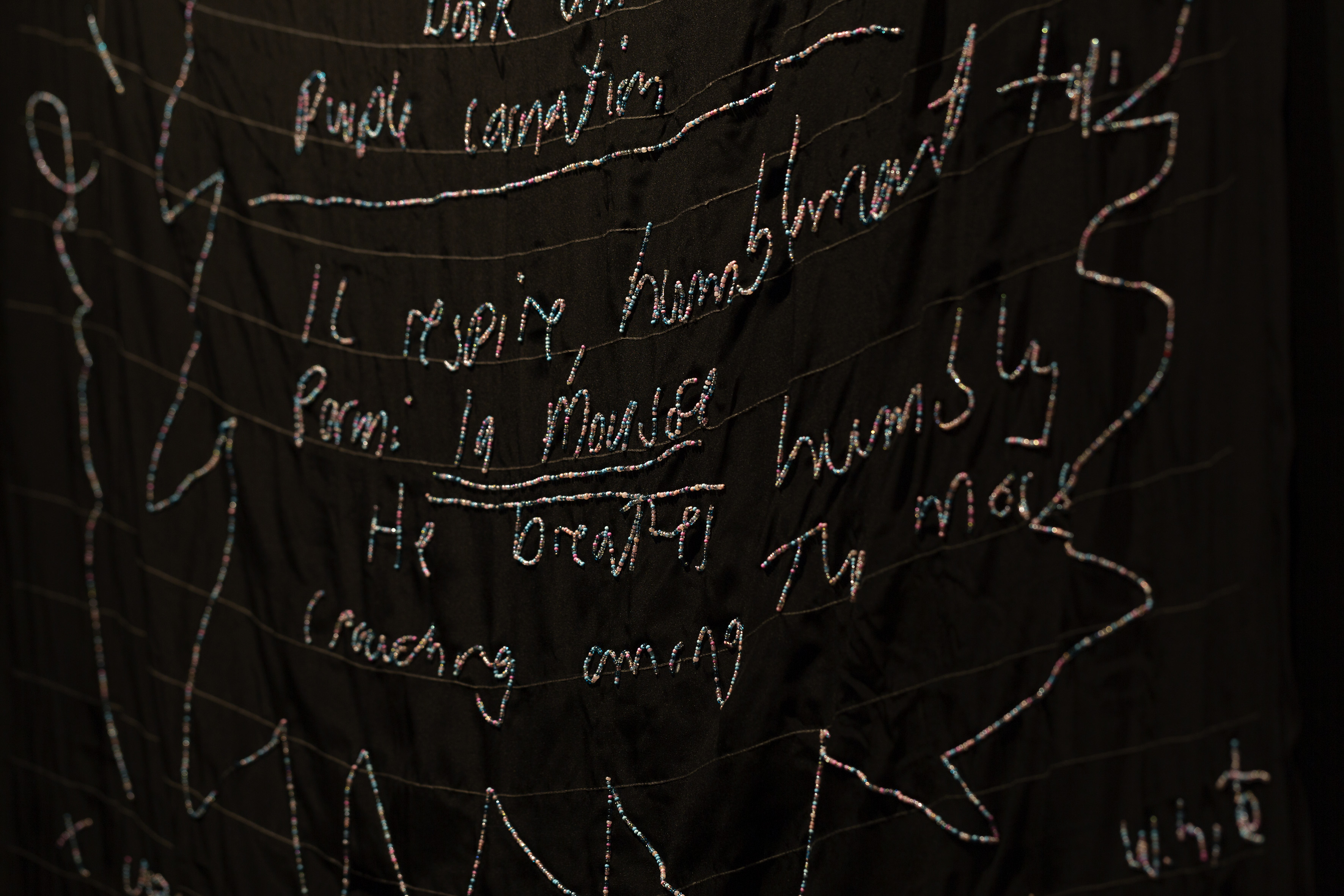

Isobel Parker Philips

March, 2020

We were walking down William Street when Sam told me about the Ghost Poo Museum. More precisely, we were walking past the Australian Museum. I only recognised the significance (or is it comic timing?) of the context in retrospect. How apt to talk makeshift museology in the shadow of a museum façade.

Unlike the Australian Museum, the Ghost Poo Museum never had a façade. Never even had a building. At most it was a box. But what more do you need? I’m not offering the etymological origins of the word ‘museum’ as anchorage here, but suffice it to say we shouldn’t be precious about the scale or sanctity of the architecture around the artefact.

So, a box. And in that box an exhibition.

The Ghost Poo Museum was a collection of calcified dog poo that Sam and a friend had stockpiled. That chalky white hard- ened stuff. Hence ‘ghost’.

The compulsion (equal parts revulsion?) was perhaps less about faecal matter than calcification. To a kid, such specimens look like fossils – motley and miscellaneous relics from an ad-hoc archaeology. Ghost poos are, after all, remnants of times past. But Sam’s scatological spoils were neither inert nor inanimate. Far from passive in their petrification, they were ghosts.

Ghosts are active; they persist, they haunt. They embody (they animate) the category of the not dead dead.

Most museums and archives are full of ghosts. Never staid, never stagnant they allow the past to surface and sneak through the cracks of chronology. When time periods entangle, histories are exhumed but also unravelled. For however codified and systematic their classification schemes, however much they uphold and entrench colonial, patriarchal and heteronormative narratives, museum collections can be uncooperative. But that’s the beauty of it. There is always mess and mischief within the museum.

The Doll Museum on the Sunshine Castle in Bli Bli, QLD is honest about its ghosts. Fierce exquisite kitsch, a castle made from besser blocks.1 The biggest in Australia apparently (who’s counting?). Probably also the only castle that is guarded by a battalion of fibreglass dinosaurs (deadset). Australian Museum eat your heart out.

You have to navigate the twists and turns of the castle’s turrets to find the Doll Museum. Or at least what’s left of it. Over the years, sections of the museum have been closed off for reparative work. Some won’t reopen, the dolls in their displays now ‘retired’ as the museum’s website states. By retired I think they mean sacrificed to the rising damp. You can still smell the mildew stranglehold a mile off.

I’ve visited the museum three times. Its slow sanitation makes me kind of sad. The feral chaos was frankly fucking beauti- ful.

These aren’t pristine ‘pageant’ dolls. They aren’t boxed Barbies or limited edition comic book characters. Sure, there’s the hyper-manicured ‘International Dancing Dolls’ display – two storeys of 1980s dioramas of animatronic dolls wearing tra- ditional dress from different countries (as you can imagine, problematic as hell) – but that’s not the museum proper. No. I’m talking about the rooms of floor to ceiling glass fronted display cabinets filled with pre-loved dolls well past their use-by dates. They are tired, they are tender and they are spectacularly terrifying. Limbs are missing, scalps are bare, eyeballs are glazed (or gone). This is where the saccharine and the sentimental comes to rot.

All items in museum collections are transformed as soon as they are catalogued. Functional objects are suddenly neutered. No longer in use, they become descriptive and illustrative. What once did now simply evokes doing. A vase, a dinosaur bone, a letter, Phar Lap’s heart – in a museum these things become echoes of their once active selves. (ghosts again). Pur- pose is purely performative.

1 I legitimately fact checked this

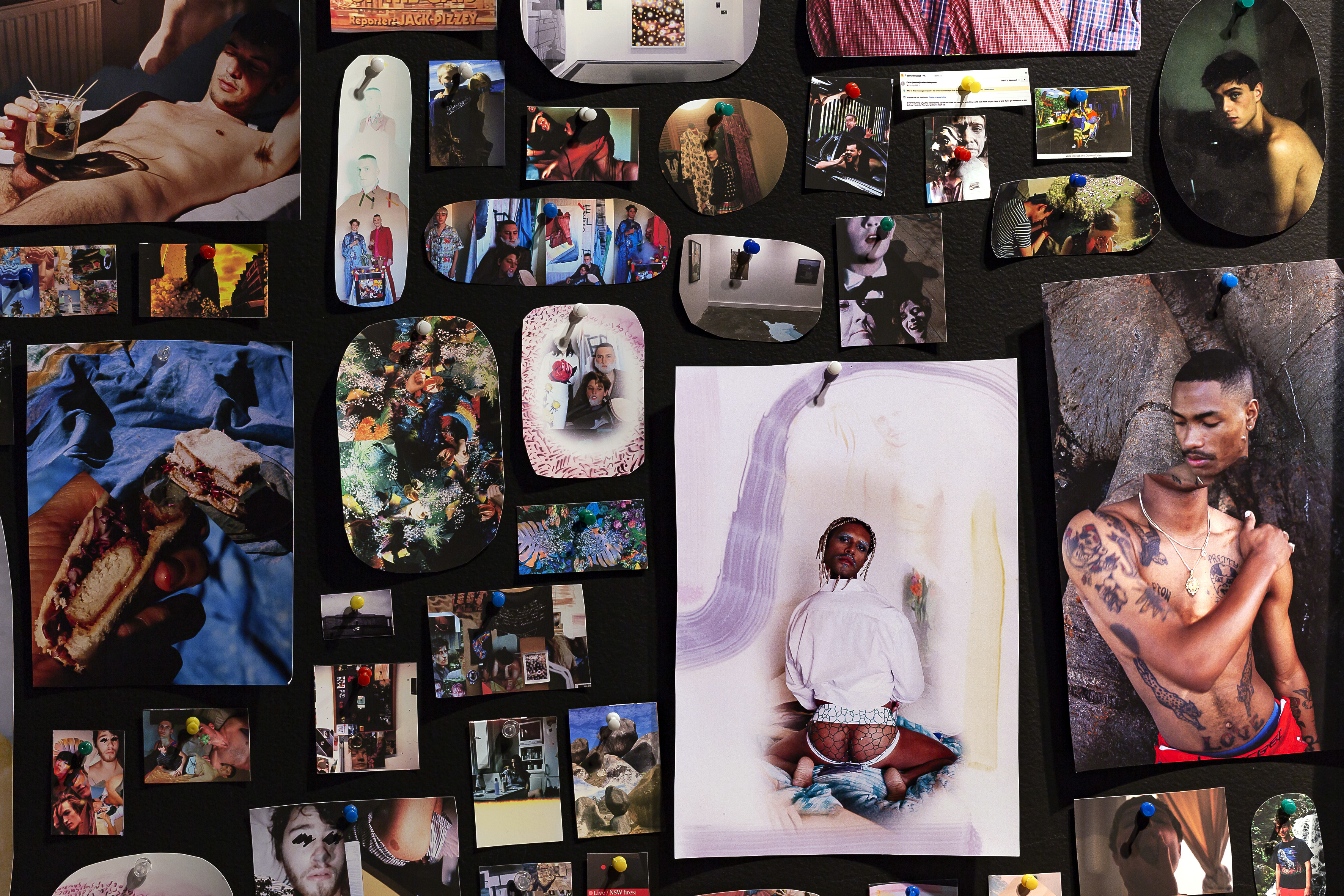

A doll’s primary function is emotive. It is affect. It is attachment. The doll museum is a museum of expired devotion. But where does that leave us, the visitors (voyeurs)? These dolls aren’t our security blankets. We cling to them differently. But the hold is still emotive. Because that’s how we navigate an archive (whether we admit it or not). We dive and delve, looking for something to stick. Something that feels familiar. Tender, even.

We all extract different meaning (different emotions) from a de-contextualised collection of objects. An archive is open slather. We undo and re-make it with every encounter. This is the mess but also the magic. One man’s trash and all that.

Sam knows how archives work. Or rather he knows how they can be reworked. Reworked and remixed, return and repeat. He knows about the treasure that can rise to the surface when you dislodge the structure and when you desynchronise. When you give in to the ghosts. But of course he knows. He saw the poetry in a piece of dog shit.